Communication Professor in The Washington Post on Lessons of WWII for COVID-19

Thursday, March 26, 2020

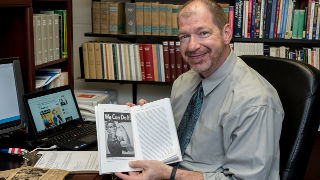

Professor Kimble specializes in studying domestic propaganda and the way it helps to construct a rhetorical community even as it fosters depictions of an enemy or other. His books, Mobilizing The Home Front: War Bonds and Domestic Propaganda and The 10¢ War: Comic Books, Propaganda, and World War II join many of his other publications in detailing the United States' use of propaganda during the World War II era to foster loyalty and support from American citizens. He is also the writer and co-producer of the movie documentary Scrappers: How the Heartland Won World War II.

Professor Kimble is, however, best known for his prior research on the WWII era icon, "Rosie the Riveter," and the identification of the model for the female figure in the "We Can Do It!" poster. The results of his work on the subject were featured by People magazine, The New York Times, Washington Post, NPR, CNN, USA Today, Fox News and media outlets across the globe, including BBC, Tribune DeGenève (French/Swiss), Europa Press (Spain), Ziare.com (Romania) the Japan Times and the South China Morning Post. Professor Kimble is also a Senior Fellow of the Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies.

In this most recent Washington Post feature, Kimble Notes the recent rise in comparisons by public figures of the COVID-19 response to the public response to WWII, Kimble notes that

These comparisons are powerful because from scrap metal drives to Rosie the Riveter and everything in between, the World War II home front was arguably as essential to winning the war as the troops themselves. But while the United States celebrates its wartime mobilization, our collective memory has forgotten the messy reality of what actually happened — and what elements of persuasion were required to mobilize people.

Though forgotten today, the home front was not seamlessly united immediately after Pearl Harbor and the populace often resisted following directions from the government. But we must remember the government’s initial struggle to sell war bonds and to overcome divisions on the home front. Recalling what it took to surmount these obstacles is essential to overcoming the medical and economic perils of the coronavirus outbreak today — which might require an even bigger effort.

Regarding the fallacy of the contemporary conception of the immediate WWII "united front," Kimble points to the data and notes,

At first, Pearl Harbor seemed to bring these divided Americans together in support of the war effort. But the wave of unity disguised continuing divisions. Throughout much of 1942, in fact, secret government polls repeatedly found nearly one-third of the country favored the idea of peace talks with the German enemy. This opposition didn’t just fade away as American troops prosecuted the war. Two years later, an American Institute of Public Opinion study revealed 66 percent of respondents believed that most of their fellow citizens were not taking the war effort seriously.

The bitter prewar split between interventionists and isolationists, in other words, didn’t vanish forever on Dec. 7, 1941. It instead reemerged in a subtler way, with a minority of citizens on one side quietly questioning the need for the war effort while those on the other side grew frustrated because they sensed the lack of commitment from this minority.

Professor Kimble also notes that "just eight months after Pearl Harbor, sales of war bonds reached a dangerous low point" and that "Early appeals to gather scrap metal for munitions production were widely ignored. Government rationing of fuel and food staples faced underground black markets. The Roosevelt administration’s plea for nonstop factory production angered many laborers, eventually fostering wildcat strikes and work stoppages."

Kimble details then how effective messaging tuned the tide:

The Treasury was forced to go to the hard sell. From late 1942 all the way to the end of the war, it staged all-out war bond drives that cajoled and hectored citizens with everything from sob stories to images of bestial enemy "rapists" to gruesome photographs of American war dead. This was part of a much larger propaganda campaign. The War Advertising Council, for example, originated in efforts to provide no-cost campaign guidance to the wartime government.

These campaigns worked, bringing the public around. The massive Treasury drives led to surges in war bond purchases. Scrap metal collections reached a crescendo. Americans even began to plant some 20 million victory gardens, providing food for their communities and ensuring the nation’s farm output could supply the military.

The Washington Post, Made by History: "The real lesson of World War II for mobilizing against covid-19: Pushing Americans to tackle a massive challenge requires far better messaging."

Categories: Health and Medicine, Nation and World